Author: redcarpet

California’s Transgender Respect, Agency and Dignity Act went into effect in January 2021, making it possible for transgender people in prison to seek housing in facilities that align with their gender identity and sense of safety. The goal: to reduce the violence, psychological trauma and degradation experienced by trans prisoners. Instead, as reported in a story that was published by KQED and republished by MindSite News, trans women transferred to the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla have suffered new forms of trauma.

As part of this collaborative project, MindSite News bring you first-person stories of life inside CCWF, drawn from interviews that journalist Lee Romney conducted with five trans women and two trans men. Where legal and chosen names differ, we’ve used chosen names. (We’ve also included a glossary of terms at the end of this page.)

While MindSite News was unable to corroborate every instance of alleged staff misconduct, you’ll find sourcing links for the most serious allegations. In a statement, CDCR said it works “to ensure those who live and work in our institutions are treated respectfully, impartially, and fairly” and “is committed to providing a safe, humane, respectful and rehabilitative environment for all incarcerated people, including the transgender, non-binary and intersex community.”

Below are the stories of the transgender prisoners who shared their experiences.

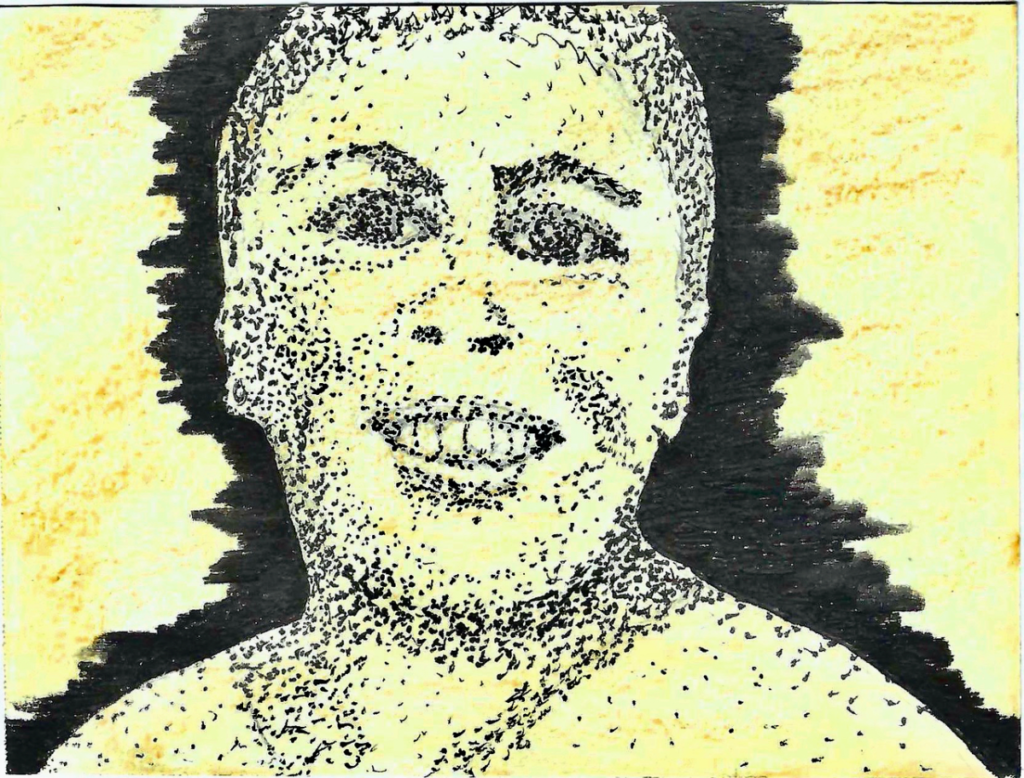

“My Mind Was Going Wild: Were These Women Gonna Accept Me?” – Michelle Kailani Calvin

Calvin was among the first trans women transferred from a men’s prison to the Central California Women’s Facility under the new law. She was thrilled and excited, but her hopes were short-lived when she discovered some guards had turned the female prisoners against her by telling them that the “men” being sent to their prison would beat and assault them. A few women left care packages for the new transgender arrivals inmates as a welcome gift, but many were suspicious. Calvin has been placed in solitary confinement on several occasions and still struggles to find her place in a hostile environment, but she hasn’t given up. Read her interview here.

Trying to Navigate This Ridiculous Pressure” – Tremayne Carroll

An incarcerated transgender woman instrumental in several prison lawsuits, one of which led to the use of video and body cameras in California state prisons, Carroll had long looked forward to a transfer from a men’s to a women’s prison. “Of course, I imagined all type of safety, I imagined all type of freedom,” she said. “Where I was at, my gender identity and who I am as a person was only my business. And coming here, I imagined being able to just be myself without having to worry about being attacked, being put in a box, assumptions being made about anything about me.” Unfortunately, that did not turn out to be the case. Over time, Carroll has been trying to figure out how to navigate the “ridiculous pressure” she feels at the Central California Women’s Facility. Read her interview here.

In Solitary and Despondent With No Release Date in Sight – Freddy “Foxy” Fox

Freddy “Foxy” Fox, 44, is an intersex transgender woman who transferred to the Central California Women’s Facility in June 2021. Keeping to herself and hoping for sanctuary from the terrible violence and white supremacist hate that she had experienced in men’s prisons, she was dismayed to find herself continually written up for false allegations, she says. She has spent nearly all of her time in solitary confinement, where she is still languishing, and currently has no access to the phone or internet.

But she still has some hope that things could change. “When the [transgender dignity] law was passed and staff actually approached me, I thought it was the answer to every prayer I’d ever had. I really did,” she says. “And there’s still potential here. There’s great potential.” Read the interview here.

“When I Started Loving Myself, I Could See Things for What They Are” – Giovanni Gonzales

Gonzales, 33, is a transgender man who says that prison saved his life. Before his transition, he said, he had no one to talk with about his challenges: “It weighed me down. Now, living my truth and being who I am, it’s like I’m free. I’m free.” That’s one reason he wants to help other transgender prisoners. Jails and prisons have a long way to go to stop discriminating against them, even for jobs, says Gonzales, who has started a transgender awareness group in his prison’s B yard. “There are a lot of staff who try to intimidate us,” he says. “But it’s important to say that a lot of the staff are alright. They do try.” Read his interview here.

Tomas Green, 35, is a transgender man at the Central California Women’s Facility. Trans men, he says, get a lot of abuse and mockery from prison officers, and the trans women are poorly treated as well. “I don’t feel that [the department of corrections] properly introduced the trans women to this facility,” he says. “They just got thrown here, like you guys deal with it, figure it out on your own. It was complicated and confusing for a lot of the cis women, like, is this a co-ed prison now? There should have been more communication – just to be more sensitive of the needs of the cisgender women. To tell them, maybe there are one or two who manipulate the system, but do not take that our on every transgender woman. Read his interview here.

“You Are Nothing Like These People Tried to Say That You Were” – Fancy Lipsey

Like many other trans women prisoners, Fancy Lipsey, 33, had been assaulted in men’s prison and was desperate to be transferred to a women’s prison. But her arrival at the Central California Women’s Facility, she says, was tainted by rumors spread by guards that the transgender women who were coming to the prison “were coming here to rape them, we were coming here to take over, we were all prison gang members.” She says she has been put in solitary confinement for things she didn’t do. She has the support of some other prisoners, who have told her she “is nothing like these people tried to say you were,” but the fear and anger stirred up among the prison population by staff, she says, has resulted in a relentless spate of unjust accusations and punishment. Read the interview here.

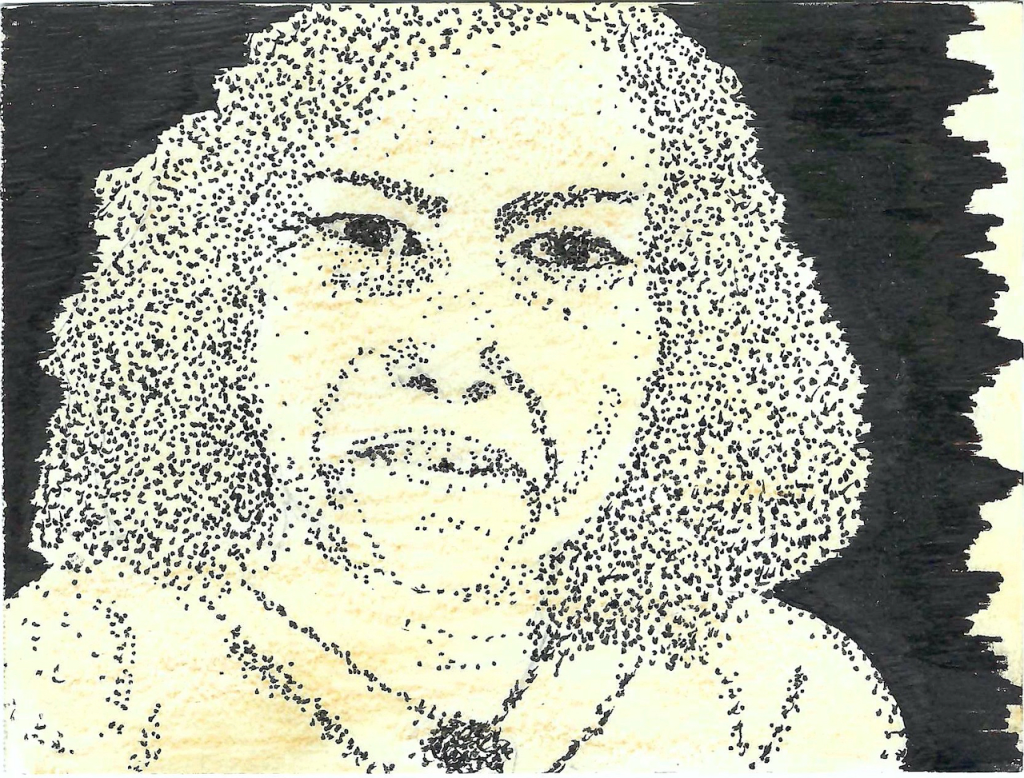

Shiloh Heavenly Quine, 64, is the first transgender woman in the U.S. to receive gender-affirming surgery while in prison. Her victory came as part of a 2015 legal settlement that opened the door for other transgender prisoners seeking gender affirming care. She is gratified that after five years at a women’s prison, she enjoys a good relationships with most of the women there, but she hopes to be released soon from prison after serving 44 years and share what she has learned with the youngsters outside. “I want to be an advocate, a person that gives back to the community to make amends for everything that has happened,” she says. “That’s my redemption. I believe in God, in a higher being, and I need to be right by him as well as my fellow human beings.” Read the interview here.

Glossary:

SB 132 – The bill number assigned to the Transgender Respect, Agency and Dignity Act before it became law in January 2021.

CDCR – California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

CCWF – Central California Women’s Prison, in Chowchilla

AdSeg – Administrative Segregation, known colloquially as solitary confinement, or the hole.

R&R – Receiving and Release

GP – general population

115 or RVR – rule violation report

602 – grievance filed by an incarcerated person

PREA – the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act. “Calling PREA” is slang for using the law to allege sexual assault, generally by another incarcerated person. Doing so has essentially ensured that prison officials would move the accused to isolation pending an investigation. However, CDCR policies around restricted housing will be changing beginning November 1 to reduce its use and provide greater opportunities to those held there.

Separation Chrono – a written document declaring that two incarcerated people cannot be placed near one another, either because they are known enemies or for other reasons.

DRB hearing – Directors Review Board, a headquarters level hearing held to determine whether to send an incarcerated person to another institution. For the trans women at CCWF, these have been held to decide whether to return them to men’s prison.

SHU – Secure Housing Unit, a more restrictive form of segregation than AdSeg

EOP – Enhanced Outpatient Treatment, a level of mental health care inside CDCR that provides treatment and specific accommodations to incarcerated people.

IAC – Inmate Advisory Council, a form of governance by incarcerated people tasked with airing concerns of the overall population with administrators.

–This series of interviews, conducted by Lee Romney and published by MindSite News, is part of a collaborative reporting project whose initial investigative story was first published by KQED and republished by MindSite News. The investigation is funded by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Latasha Brown sat at a picnic table in the visiting area of the California Institution for Women, just out of earshot of a guard standing watch. It was a hot morning in July and the 42-year-old spoke softly.

“There’s liberty in deciding not to live in fear any more,” she said.

Brown was speaking out for the first time about the sexual abuse she has suffered at the hands of correctional officers over her 21 years in California prisons.

Once she started talking, she couldn’t stop: there was the officer who watched her shower, the official who demanded sexual favors in exchange for legal help, the officers who forced themselves on her and then gave her small “gifts”. Brown says she has been sexually assaulted by at least five correctional officers during her time behind bars, and harassed by many more: “We’re not only prisoners in here, we’re women, and we’re reminded of that through widespread male violence.”

In May, one of those guards, the former officer Gregory Rodriguez, was charged with nearly 100 counts of sexual violence. Authorities say Rodriguez is suspected of harassing, assaulting and raping at least 22 women in custody from 2014 to 2022, though court records and testimony from women and their lawyers suggest his abuse extends beyond the criminal allegations. Rodriguez has pleaded not guilty to all charges, and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.

Five of the women who have come forward about Rodriguez say the abuse left them with lasting psychological distress that they’ve struggled to overcome in prison. They describe a system in which a lack of access to basic amenities like adequate food and hygiene products and regular family communication make them vulnerable to abuse by guards who promise privileges or threaten further restrictions. Abuse is so widespread it can feel inescapable and ordinary, women said, noting that they face immense pressure to stay silent, living with the stress of potentially lengthened sentences or solitary confinement if staff retaliate.

‘He groomed me’

Brown has been incarcerated for more than two decades, sentenced to 37 years to life for a murder she committed at age 15. She says was sexually abused as a child and again in county jail before she was sent to California’s women’s prisons. Brown has spent time at both CIW, an hour east of Los Angeles, and the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla, where Rodriguez worked.

Predatory guards take advantage of the lack of supplies and conveniences, making women dependent on them for items they either need to survive or simply to feel normal, Brown said: “As prisoners, our possessions are everything. What little we have is so important to us.”

Two officers who groped and assaulted her over the last decade would give her clothing to bribe her into silence, she continued, including bras and a bandana. One of the guards repeatedly fondled her at her prison job and then left her small presents in a trashcan not visible to cameras, she said. She remembers thinking of one of the guards as “generous”: “I’m deeply ashamed of it, but I also knew there was no recourse for us.”

Valerie*, an incarcerated woman in her 30s who says she was repeatedly abused by Rodriguez in 2014, said he at first presented himself as one of the kind officers. When she arrived at CCWF, she felt alone and was often by herself, she said.

“When I think about how he groomed me, it wasn’t that he was forceful in the beginning. He was just a friendly face, always asking me how I was,” she recalled. “We appreciate the nice staff, because they’re the ones that treat us like humans. He positioned himself that way. I thought he cared … when really I was just being manipulated.”

Over time, Rodriguez started sexually assaulting her in unmonitored areas, she said, and pressured her to tell no one, warning that if anyone else knew, she’d face trouble. He suggested that would make it harder to get parole, she said: “‘You don’t want to be in that position because you want to go home.’”

She said she wanted the assaults to end, but was terrified of retaliation: “At that time, I felt I was responsible for all of the abuse … I just felt trapped because I couldn’t talk to anybody.”

‘We can’t defend ourselves’

The case against Rodriguez has sparked outrage in California, but data suggests the women’s experiences are incredibly common. The last national survey of incarcerated people by the justice department, conducted in 2011 and 2012, counted roughly 47,000 people who had been sexually abused by staff in the previous 12 months, though the number is a significant undercount. The California department of corrections and rehabilitation (CDCR), which imprisons nearly 4,000 women, logged more than 800 complaints of staff sexual abuse across the state last year.

“They say it’s one bad apple, but it’s not,” said Brown. “The abuse of prisoners is widespread but has largely gone unacknowledged.”

Brown said she was working as an aide for women with disabilities last year and was bringing a woman in a wheelchair into a parole hearing room when Rodriguez opened the door and rubbed his body on hers as she passed through – an assault he repeated on a second visit. She had not reported her previous assaults and didn’t want to disclose this one, either: “There is shame and stigma attached to being not just a victim, but a snitch. So I’ve learned how to fly under the radar and stay quiet. These people hold my life in their hands and I know the lengths they will go to cover up misconduct. I’ve watched officers turn a blind eye to the conduct of their peers or facilitate attacks on other inmates. All I know is how to survive.”

When abuse did become known, the consequences for women often were severe. Both Brown and Valerie say they were placed in solitary after staff found out about Rodriguez’s assaults on them. CDCR says women who report abuse are placed in “administrative segregation” for their safety and when no other housing options are available.

Selina*, who reported that Rodriguez sexually assaulted her and who has testified for the prosecution, said she lived with daily fear that more people would find out she was a whistleblower and that she would face retaliation or violence as a result; she does not talk to her prison counselor about what she’s been through. When any officer makes a snide remark at her or looks at her in a certain way, she panics, she said.

“The only thing they could really do to keep me safe is to get me out of here,” she said. “We can’t defend ourselves in here, because who is going to listen to us? We’re a number in here. We’re not treated like people. I just want to get home to my kids.”

‘I internalized my anger’

The psychological toll of repeated sexual abuse in prison can be severe. Survivors of sexual assault described an intense struggle with shame, anxiety, fear, depression, suicidal ideation and post-traumatic stress from living in an environment where abuse was normalized.

Compounding their challenges, many women who are incarcerated have already experienced trauma in their past. Studies in the US have found that 60% to 80% of incarcerated women experienced sexual violence or domestic abuse before they were jailed, making them especially vulnerable to revictimization.

Several survivors described severe discomfort in confined spaces and feeling scared when anyone gets too physically close – triggers that are impossible to escape in prison. Brown said she felt trapped in a state of “permanent alert” and “perpetual uneasiness”; when anyone approaches her from behind, even a cellmate who is not threatening, it makes her body jump and her heart race. Recently a supervisor whispered something to her while trying to be quiet, and it caused her to panic.

Brown said that when she read old journal entries talking of the abuse, “I feel so sad for her. I minimize the abuse to distance myself.”

Rita*, a 36-year-old woman who says Rodriguez assaulted her while she was incarcerated at CCWF, said that she had been sexually abused as a child and was so shaken and retraumatized by his attack that in the moment she almost physically fought back: “But instead I just shut down, because that was my coping mechanism when it happened to me as a child. And I felt like I was a child again.” She was recently released and has struggled at her first job post-prison, where she has to work in close quarters with male employees.

Survivors have few or no outlets to process their trauma, said Amika Mota, executive director of Sister Warriors Freedom Coalition, a non-profit group that works with incarcerated survivors, including victims in the Rodriguez case. “So many incarcerated people have never had access to any mental health support, so they hold so much within.”

Mota recently testified about her own experience of abuse inside California prisons and is part of a newly formed CDCR committee focused on preventing sexual violence. “The narrative we are fed – that if you speak up, you are no good, you are a ‘snitch’ – it becomes so internalized. Not speaking up becomes like a badge that we wear. The impact is that you begin to choke on your own voice when you start to use it.”

“I really internalized that anger towards myself,” said Valerie. “I really did feel like I brought this on myself, and I tried to deny that it happened … I felt dirty and did not know how to get rid of that filth.” She eventually became an educator, teaching her peers about sexual assault policies, which she said helped her speak out and learn to set boundaries.

‘I will not bow down’

CDCR declined multiple interview requests over several weeks. A spokesperson, Terri Hardy, said in an email that the department “investigates all allegations of sexual abuse, staff sexual misconduct, and sexual harassment pursuant to its zero-tolerance policy and as mandated by the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act”. The policy “also provides guidelines for the prevention, detection, response, investigation, and tracking of allegations against incarcerated people”, she said.

Rodriguez’s arrest, Hardy added, followed CDCR’s internal investigation and referral to prosecutors: “The department resolutely condemns any staff member – especially a peace officer who is entrusted to enforce the law – who violates their oath and shatters the trust of the public.”

Brown, one of the first to speak publicly about Rodriguez, said she knew there were risks in coming forward, but that it was empowering to no longer stay quiet: “I am guilty of the worst of human behavior. But just because I’m in prison does not mean my body and my labor are interchangeable properties.” She also agreed to testify before a recent hearing of lawmakers and CDCR leaders. Although officials declined to allow her to speak live, an advocate read her remarks, in which she recounted the moment she learned of Rodriguez’s arrest.

“I did not celebrate because sure, when we experience harm, we want some accountability. Some justice, even,” she said. “However, I don’t think his punishment should be the final resolution because it’s an amplified response to just one person’s abuse, not a response to the systemic abuse. And until our lives matter, I will not bow down.”

*Valerie, Rita and Selina are pseudonyms to protect their identities as sexual assault survivors who fear further retaliation

TAKE ACTION

CDCR SEXUAL ABUSE ADVOCACY TOOLKIT

Real News Interview with CCWP Advocate Erin Neff about sexual abuse at FCI Dublin

A recent investigation into sexual abuse at a women’s federal prison in Dublin, California, brought down several guards and the prison’s former warden, Ray J. Garcia. But a new lawsuit from eight women now alleges that the investigation has not stopped the culture of sexual abuse. Erin Neff of the California Coalition for Women’s Prisoners joins Rattling the Bars to discuss the new lawsuit and the underlying culture of sexual abuse found throughout US prisons.

Studio: Cameron Granadino, David Hebden

Post-Production: Cameron Granadino

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Mansa Musa:

Welcome to this edition of Rattling the Bars, I’m your host Mansa Musa. Do you know who Joan Little was? Joan Little was charged with the 1974 murder of Clarence Alligood, a White prison guard at Beaufort County Jail in Washington, North Carolina, who attempted to rape Little before she could escape. Little was the first woman in United States history to be acquitted using the defense that she used deadly force to resist sexual assault. Recently, eight female prisoners, dubbed the Rape Club by prisoners and correctional staff alike, found a lawsuit against the Federal Bureau of Prison arguing that sexual abuse and exploitation have not stopped in Dublin FCI, despite the prosecution of former warden and several former officers.

The lawsuit filed in Oakland by attorneys representing prison and the advocacy group California Coalition for Women Prisoners also named the current warden and 12 former and current guards. It alleged the Bureau of Prison and staff at Dublin Facility didn’t do enough to prevent sexual abuse going back to 1990. An Associated Press investigation last year found a culture of abuse and coverups that persisted for years at the prison. What does the #MeToo movement garnering public attention mean in terms of obtaining justice and relief for incarcerated women? Here to talk about the current state of Dublin FCI and related issues is Erin Neff, who is a legal advocate with California Coalition for Women Prisoners. Welcome to Rattling the Bars.

Erin Neff:

Thank you, Mansa, good to be here.

Mansa Musa:

Tell our audience a little bit about yourself.

Erin Neff:

My name’s Erin Neff, I work with California Coalition for Women Prisoners. We are a grassroots organization that has been active in the California prisons for the last 28 years. We began at Chowchilla with the CDCR giving support to a woman named Charisse Shumate, who was advocating for the lack of medical care. Since then, she actually did not survive her illness, but she began a movement with us, with people on the outside to create advocacy relationships. We have been working mostly with the CDCR system in the women’s prison system, and we are currently in the last few years working at FCI Dublin.

Mansa Musa:

Okay. Now recently, an article came out or information came out about the current state of Dublin Prison in Oakland, California, or in the Bay Area, as it relates to female prisoners being abused, sexually abused. We know that in the federal prison system they have what’s known as PREA, Prison Reform Enforcement Rape Act, I think that’s what it stands for, but the concept of PREA is that anyone under the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prison, anyone under any state or local facility that has an issue about being sexually abused or sexually assaulted by either inmates or staff, they have this mechanism where they can immediately contact someone, had a person allegedly done something to them removed from the institution and have the person that’s making the allegation removed from the institution, and then an investigation going on, and in the interim of that, until that is resolved, these people are never put in the place together.

But now, come to find out that in California, in Dublin in particular, in terms of this particular incident, it’s known that this is far more reaching than just in Dublin Prison, this is a … I think I read somewhere that say it’s the culture of the prison system. Talk about Dublin first, let’s talk about that and what’s going on as far as the lawsuit and how this came about, and if you can give historical context to it, if you have one.

Erin Neff:

Yeah. So PREA is the Prison Rape Elimination Act, and that should generally give a person who is experiencing sexual harassment or abuse a way to confidentially report this abuse, and that appropriate action and investigation will be taken against this person who is doing the abuse. In the case of Dublin, just to give it a historical context, 30 years ago there was a horrific incident of abuse on many people, and there was a big case and a big settlement, and it is heartbreaking to see that 30 years later the same thing is happening. What it exposes is a culture of turning a blind eye to this abuse, there’s cooperation, there’s coverup, there is very difficult to report, let alone confidentially report.

So in recent times, what you’re seeing are people being abused who are undocumented. So first of all, they are being targeted because the staff knows that they are people who are going to be deported. So there is an exposure there. They are threatened that if they say anything they’ll be deported, so these people are people who’ve been here maybe their entire lives, all of their family’s here. So the possibility that they will be deported, and I’m sure this staff lets them think that they have some sort of power as to whether they can stay or go, so there’s that. They’re being retaliated against by putting in isolation, they are getting strip searched, it goes on and on. They’re being deprived of medical care, of mental healthcare. These people have really suffered tremendous abuse, and on top of this abuse they’re being punished again by not getting the medication that they were once taking. That is a very common scenario where their medication that helped them survive in this place of incarceration, they’re not getting the medical care, they’re not getting counseling.

In some cases, reports where they’ll get minimal counseling, but it’s with a man who is part of the staff, they do not feel safe at all. Their commissary is getting limited, harassment in the middle of the night. It goes on and on and on. While this has been exposed, Warden Garcia was found guilty and sentenced to 70 months for his abuse, this ongoing abuse. There was a chaplain, multiple correctional officers, the counselors who were cooperating and giving information to those who were abusing and they’re giving people away to target people who are more vulnerable, those for example who were undocumented. So you’re seeing people transferred out of state if they do report, so they’re getting transferred away from their families and their communities. It goes on and on and on.

Mansa Musa:

We’re not talking about Orange is the New Black, we’re not talking about some HBO theoretical or theatrical rendition of what an ideal prison would look like in America. We’re actually talking about real live human beings. But talk about the lawsuit, so now we’ve reached critical mass to the point where we have a lawsuit, talk about the lawsuit and in talking about the lawsuit, has an injunction been leveled against the institution to cease and desist? How are you able to get coverage for these women? Because as I said earlier, as you outlined, that type of fear permeates the population.

When you’re in the prison, and I’ve been in prison myself, I did 48 years, when you’re in the prison environment and you don’t have no control whatsoever to begin with, but the isolation really makes you feel like you don’t have no rights, and whatever’s going to go on with you that day or that period in time, either you’re going to accept it or you’re going to die trying to defend yourself. But at any rate, you’re going to be subjected to some harsh, cruel, brutal treatment, or mistreatment. Talk about the lawsuit, if an injunction is in effect, and how do these women get coverage where they can get a sense of security?

Erin Neff:

Yeah. So CCWP is the organizational plaintiff for this case against the BOP, along with many individuals. Currently, where it stands is we are waiting for a response from the BOP, it’s currently a bit in what feels like stalling stage on their part, before the trial will be granted. So we are waiting on that. In the meantime, anyone who is part of this lawsuit is also currently incarcerated, some people have been released, but many are still incarcerated at Dublin or transferred. People that I am visiting are talking about being treated as less than human. Last week I sat across from someone who is being denied her medical care, her mental healthcare, she feels completely forgotten, she feels completely hopeless, she’s been subjected to isolation.

This is a real person with children, she speaks to her children and her children are so worried about her because of her feeling of hopelessness. She’s already paying for her debt to society, she’s doing her time, and on top of that she is being treated as less than human. This isn’t a TV show, these are real people. The effect on that individual, the effect on their families, their children, it’s not isolated to that one person. So the hopelessness is very hard to fight against. What we try to do is educate them and inform them of what we are doing on the outside, and that they are not forgotten. They did recently say that they saw us when we filed the lawsuit, and we had a demonstration out in front of the courthouse in Oakland, and that was extremely empowering for them to know that people are active and that we are fighting.

Mansa Musa:

Like you said, this is not no TV show, this is not no, “Wait, go back, act like you’re distraught. Wait, go back, put more emotion.” No, this is real life. Speaking on the outside, and this is just my perspective, and we’re talking about California and we’re talking about the Bay Area, but we’re also talking about a state where if these women were in Paramount Studio, if these women was in some major corporation, if these women was in anywhere in society being subjected to this, the #MeToo movement, the feminist movement, every ambulance-chasing lawyer would be outraged, would be in uproar, would be identifying the warden, the corporate leader and trying to get charges against him, trying to get him locked up, trying to get their money, a lien on their moneys. Do you feel like that it’s a disconnect between these movements and women that are incarcerated? If so, why? If you can talk about that.

Erin Neff:

Well, yes, there’s a huge disconnect, even in the Bay Area people are not aware that this is going on. Unfortunately, what you see in the prisons, everyone knows, is we see Brown people, Black people and poor people, people who are already vulnerable, people who have suffered a tremendous abuse, and a blind eye is turned to these people. This is a capitalist society where we value people who are seemingly of value, and it’s a very, very tragic view even in California, where we are the most liberal state. We see people turning away from this, it’s incredibly painful to see that truth. People don’t want to see that, they don’t want to know that is happening in California.

Yeah. If you see someone on the outside, not to minimize the tragedy of that recent expedition to go see the Titanic, these millionaires, billionaires spent a ton of money and very tragically they died in this accident. You see an outpouring of interest and focus on this. Why are these people who are incarcerated of less human value?

Mansa Musa:

Right. Let’s give a context to people that are incarcerated, because according to the judicial system and according to criminal law, we have what we call crime and punishment. A person’s charged with a crime, the punishment they get is the amount of time they are to serve, not how they serve their time, the amount of time. If I do robbery, if I rob somebody and robbery incurs 10 years, the crime is I committed a robbery, the punishment is the 10 years. The punishment is not, “I’m sentencing you to 10 years to go be raped, sodomized, brutalized, terrorized, and then released.” The punishment is that I’m going to be sent to an institution, the next phase in my sentencing process is and the narrative is that I’ll be sentenced to an institution that’s going to provide me with the means and the mechanism to make the adjustment for my ultimate return to society.

Not where I’ll be subjected to, as a female, more importantly than anything else, be subjected to coming into an institution and the way the prisons are, this is the prison culture in terms of how we look at people that’s incarcerated, we know the institutions they be going to, we know the way the institutions are ran, we know what goes on in these institutions, probably even get there. They say, “Oh, yeah. You’re going to Dublin.” The first thing I know is, “Okay, I know that this is the way …” There’s real abuse like this here, women are being … I’ve got to be on the lookout for this, I’ve got to be on the lookout for that. Automatically what happens is once I get into this environment, I’m automatically on the defense because I recognize that the abuse about the environment proceeded itself.

But talk about the women, and you talked about earlier about how some of the clients that you deal with are really being depressed, and rightly so. But talk about how we’re able to get them to hold on and have faith and be more spirited about the fact that, not only this too going to pass, but the people that’s responsible are going to be held accountable. That’s a fact. We know that based on y’all organization and y’all organizing. But talk about how you are able to get them to hold on and recognize that they’re not wrong for wanting to be human, they’re not wrong for expressing their desire for their humanity. The people that’s wrong is the people that’s abusing them, that’s being given the authority to abuse them.

Erin Neff:

That’s right, yes. It’s an excellent point. The punishment is the time you do, and your time in prison is supposed to include opportunities for rehabilitation. That is another thing that people are allowed to do programming, and this programming can include AA, NA, ways to improve yourself, codependency. This is another form of retaliation in that they deprive you of getting to take those classes and be in groups and in community. So you are being doubly punished. What we try to do, we have in-person visiting where we are trying to meet as many people as possible and let them know that we are here. We have a writing relationship with them, they have access to email where we start being in contact as much as possible. We use this as an opportunity to find out what is going on inside.

Now, no email or phone calls are confidential, so it’s not a guarantee that we can exchange real information. We have also a newsletter called the Fire Inside that CCWP has been publishing for 28 years. We have three issues a year. We’re send those to people in CDCR as well as the FCI Dublin, it’s in Spanish and in English. We solicit information and content and poetry and stories from them to get their stories out, so that they are heard. Last week in my visit I shared the newsletter with many people, and it was great because it’s also in Spanish, and I think it was-

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Erin Neff:

Tragically, they are so moved because they are not used to having people acknowledge their existence and their suffering.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, go ahead. Go ahead.

Erin Neff:

So the fact that that is happening and we are giving them voice, we want to know what’s going on, we really want them to know that their stories are incredibly important and they are not suffering alone. Sometimes the only thing that we can do is write a letter and say, “We are here. How is your day going?” That can make a huge difference. But things like the lawsuit is incredibly important. A demonstration in front of the courthouse when the case gets filed, these things are incredibly important because it does get inside.

Mansa Musa:

We want people to recognize that we’re talking about human beings, first of all, we’re talking about people, human beings, but more importantly we’re talking about women. The fact that in this society we deal with chauvinists, sexists, racists, bigoted society, capitalist society, the fact that these things exist seems to overshadow what we’re talking about when we’re talking about people that were sentenced to serve time, the judge did not say when sentencing them, “I’m sentencing you to 10 years in Dublin Federal Correctional Institution to be raped, sodomized and brutalized, dehumanized, and hopefully by the time that you return to society you’ll be a shell of a woman.” No, the judge sentenced these people, sentenced these women to a term of imprisonment and to be rehabilitated.

But Erin, you’ve got the last word on this here, how do we get in touch with you? What do you want our viewers to take away from this here? More importantly, when you go back and talk to the sisters, tell them we send our solidarity out and big hugs.

Erin Neff:

Thank you so much. Thank you also doing the shout-out to women who are just a more vulnerable population. Most of the time women end up in prison, have been system impacted, or they have been abused or trafficked, and end up in these situations where they’re getting abused even more. If you would like to get in touch with California Coalition for Women Prisoners, we have an advocacy program where we join people on the outside who are interested in reaching this population and doing advocacy and learning from the ground up. We are a grassroots organization, you can look at WomenPrisoners.org and send us an email and we will get you connected. We have orientations and trainings, bimonthly meetings to support you in this work. It is a really big community of amazing, amazing organizers and people with tremendous heart to recognize that this problem, while isolated to what’s happening inside of a building, inside of a prison, is impacting all of our lives.

Our communities are being impacted, your neighbor is being impacted. Whether you feel it directly or not, it is. It’s welcome-everyone and please come and check us out. WomenPrisoners.org. The women at the FCI Dublin would love to be in touch with you.

Mansa Musa:

Thank you, Erin. There you have it, the Real News, Rattling the Bars. Are you rattling the bars today? We see an event where the person threw their hat up in the air, and when he threw his hat up in the air it was a moment where everybody came around and supported. This is that kind of time. This is a throw-your-hat-up-in-the-air moment for women incarcerated throughout the United States of America, more so importantly in Dublin. Nobody has the right, nobody has the right, nobody has the right to violate your body. Nobody has the right, because you’re serving a sentence, to come in and say, “Because you’re serving time, or because you’re considered an illegal alien, or because you’re a woman that I have a right to subject you to the most dehumanizing, inhumane treatment, only because I got the authority. I got the right to rape you. I got the right to sodomize you. I got the right to deny you your medication. I got the right to deny you food. I got the right.”

No, you do not have the right. You do not have the right. The right is not given to you. The right that you have is to ensure that I’m in a safe environment, and when you subject women to this cruel and unusual punishment, you’re going to be held accountable. We see this being taken place now by the work that Erin and the sisters and brothers in California are doing. We ask you to continue to support the Real News and Rattling the Bars. It’s only from the Real News and Rattling the Bars that you’re going to get this kind of information. You’re not going to get this information on ABC or CBS or NBC News. You’re not going to get this information from someone from the White House getting on a platform saying, “Yes, we find it’s problematic that women are being raped in prison and women are being sodomized in prison, and that we’re paying money for this to make sure that they do it with impunity.”

No, you’ll only get this information from the Real News and Rattling the Bars, and we ask that you look at this report. We ask that you investigate what’s going on in the prison system, and particularly in California. We ask that you take a stand. If you believe that raping people, sodomizing people and abusing people are a good thing to do because they was convicted of a crime, then weigh in on that. But understand this here, if they come for me in the morning, they’ll come for you at night. So you’re not immune to it, you will be subjected to the same harsh treatment when it goes unchecked. Thank you, thank you very much, Erin, and thank you for listening.

The Lived Experience of Long-Term Sentences in California Women’s Prisons

The University of California Sentencing Project (UCSP), in collaboration with the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) and the UCLA Center for the Study of Women|Streisand Center, is proud to announce the release of its groundbreaking report: “Maximizing Time, Maximizing Punishment: The Lived Experience of Long-Term Sentences in California Women’s Prisons.”

|

|

|